I have always been convinced that objects in general look like living beings. As a kid, one of my favorite practices was to imagine that each car has a face, sometimes happy and laughing and some other times sad or even angry. I grew up, studied architecture, and started to apply this practice to buildings. I imagined that they were talking to me. They can transmit several vibes and emotions. Just a first glance at any building can put you at ease and make you feel welcome or afraid and rejected even before you start using it.

Any architect or designer would link this phenomenon to the characters and qualities of lines and shapes we use in designing any object or building. A straight line will signal someone is stable, balanced, and sharp. A curvy line will appear playful, at ease, and calm. While a jagged one will look angry, confused, and in a rush.

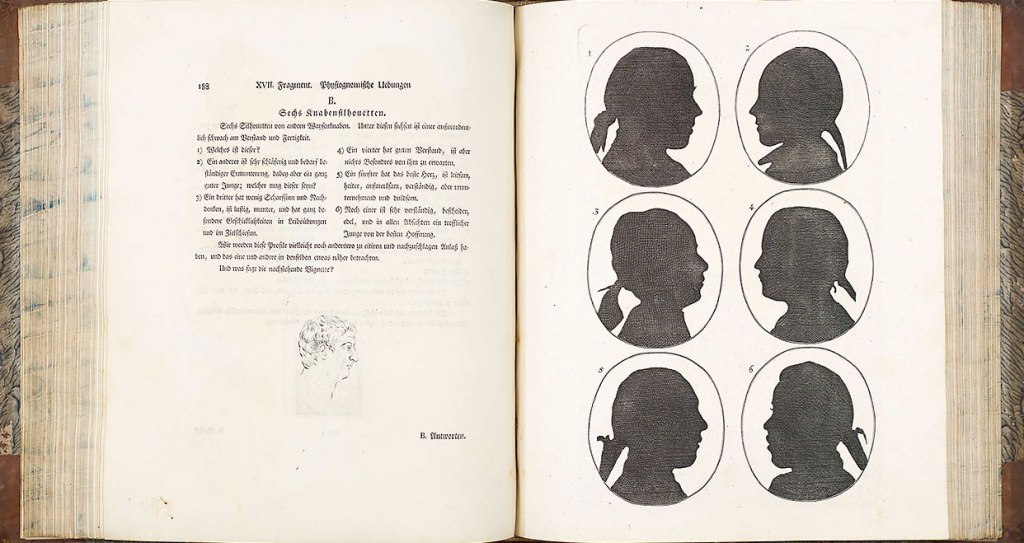

But this practice can also be linked to(in Arabic علم الفراسة) or Physiognomy. The word comes from Greek: physis meaning “nature” and gnomon meaning “judge” which is the practice of assessing a person’s character or personality from their outer appearance, especially the face. Between 1775 and 1778 the Swiss writer and poet Johann Kaspar Lavater published the Physiognomische Fragmente zur Beförderung der Menschenkenntnis und Menschenliebe (Essays on physiognomy). Lavater used a pseudo-scientific system to judge human character from physiognomy. “ He analyzed almost every conceivable connotation of facial features and supplied line drawings with interpretative adjectives appended to each illustration”, recited from The Architecture of Happiness.

The practice of linking buildings and objects to humans first appeared in the works of the Roman author and architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio when he imagined that each of the five major orders in architecture (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian, Tuscan, and Composite) has its trait that makes it resemble a specific human.